Summary: This blog post examines the rationality behind the recurring behavior of firms not willing to accept the wage inflation in case of their existing employees (ie. “urging” them to leave by keeping them at a flat comp for years) while paying the (much higher) market price for the backfills. Is this the right thing to do or it hurts the company’s bottom line in the long run?

It’s been bugging me for years when I lose a colleague in the middle of a project for compensation reasons, spend significant time and effort to recruit and bring up to speed the backfill while I know that the compensation of the new hire is higher than the money that the departed person would have stayed for. Counteroffers after the resignation are mostly in vain, by the time the employee resigns she is emotionally disconnected. But the most damaging is when the employee leaves as an individual contributor (IC) and then returns as an officer within a year because she does not fit in the IC pay range anymore (a smack in the face of the merit-based promotion process). At some firms the problem even has a telling name: “Loyalty tax”.

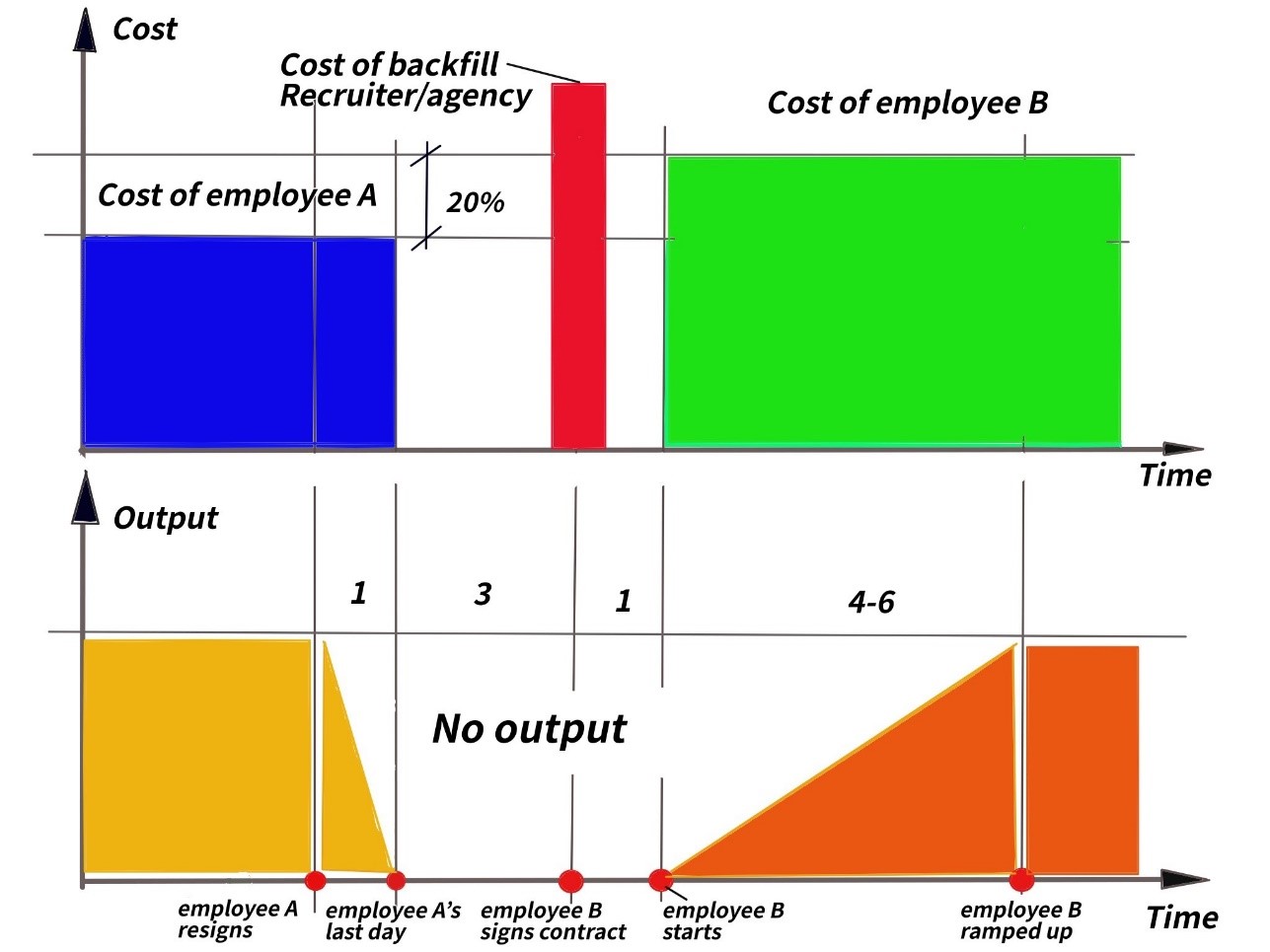

The output and compensation math of these backfills looks like this (pls. find the assumptions I used in Appendix A):

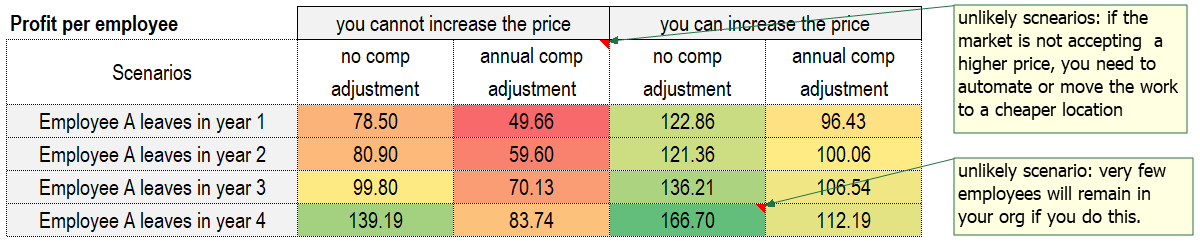

For the first look it seems obvious that attrition hurts delivery and costs a lot to backfill, so if we know that the root cause is compensation related, it makes sense to increase the salaries. If this is correct, then why companies do it so grudgingly? To prove this theory, I built a model to see what happens to one’s profitability if she increases the compensation of the existing staff to make them stay longer. (Pls. find the parameters in Appendix B.)

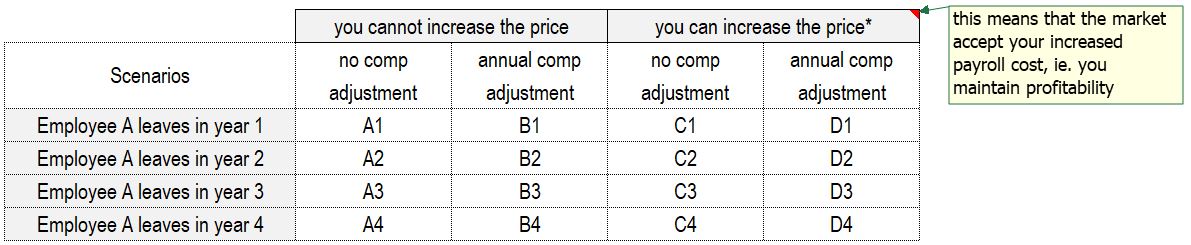

I created scenarios along the lines:

- a firm can maintain its profitability while the payroll increases. (y/n)

- Is willing to share this extra revenue with its employees to make them stay longer. (y/n)

- Some condition will change within max 4 years (function, manager, location, private status), therefore we will no longer compare apples to apples. Hence the cut-off at 4 years)

Here is what I ended up with:

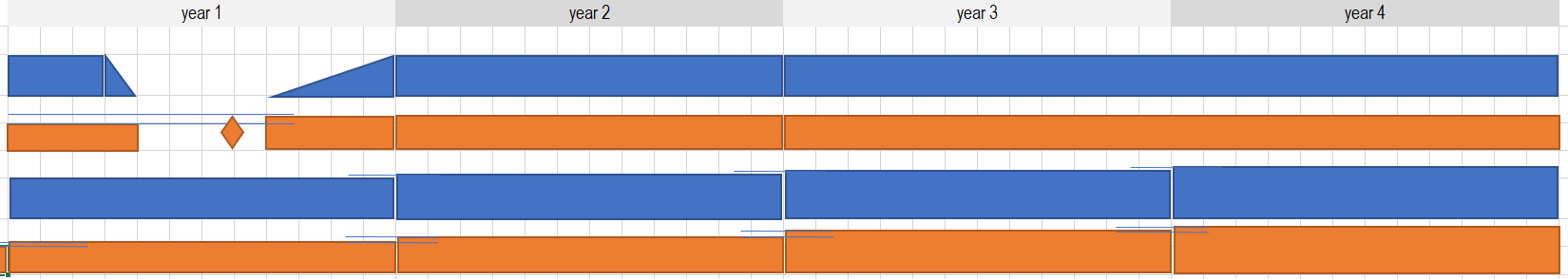

Pls. find two illustrations below to Scenario A1 when the employee leaves in the middle of year 1, and the honky-dory scenario when the firm maintains profitability, shares it with the employee, so she stays for 4 years.

- “A” scenarios: most firms will not increase comp when the market is not willing to pay more for their stuff. In this case the firm either automates as many functions as it can, moves the bulk of the development into nearshore or offshore development centers (this is the driving force behind bringing IT jobs to Eastern Europe), imports cheaper workforce from other countries OR accepts less qualified backfills.

- “B” scenarios: the firm cannot increase its prices but must adjust the payroll. Firms hate this thing and do it only as a last resort, eg. with a fixed fee support contract where the client fences off cheaper alternatives. Other examples are when the employee has monopoly on skills or expertise, ie. has a strong negotiating position. (cannot be replaced easily.)

- “C” scenarios: this is the best option to the firms – increase the prices while keep the payroll flat as long as your employees are willing to accept it. This may work during economy downturns.

- “D” scenarios: this is when the firm is willing to split the extra revenue with its employees. This looks like the optimum solution; find a split that both parties accept, then focus on the motivation factors. The dilemma is how to make sure that the extra money has an impact.

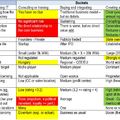

The following numbers are based on fictive cost and revenue components, the point is their relative size and how they react to changes in the inputs. You can find the model on this link: Wage inflation v2

I have doubts about applying the bell curve to small populations, then moaning about the consequences of forced ranking, but i maintain a view that in an ideal case a firm has a clear understanding on the achievements and the future potential of its people. In this case i would pick the midpoint between the consumer price index and the wage inflation and would disperse this increase to the upper 50% of the staff, tilted towards the top 25%.

There are cases when your employees do not leave but lack intrinsic motivation to do their best (eg. watch Youtube for hours or come in at 11AM). Several top brains - Herzberg (two factor theory), Deci & Ryan (self-determination theory), Dan Pink, Seth Godin to name a few – have proven that money itself does not cut it.

Most departures are caused by multiple factors, not just money. BUT: a good developer is approached by recruiters on a monthly basis, temptation to listen to their siren song increases with the time not receiving any uptick in base comp.

Bottom line: Covering at least the inflation for good performers makes sense. (the objectivity of performance evaluation could be another post☹) As always, I will be glad to receive comments on this post.

Appendix A - Assumptions

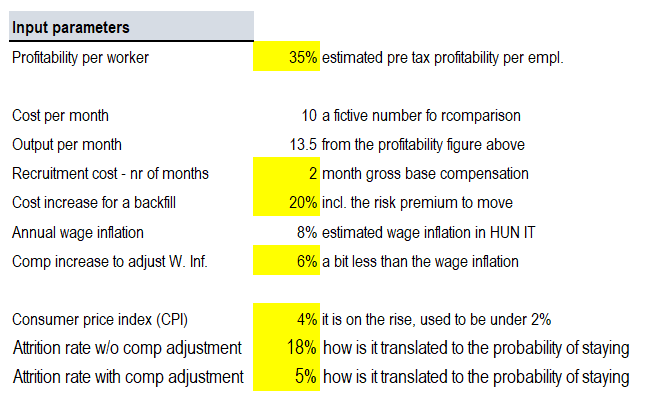

I made assumptions here, that are reasonable for Hungarian developer jobs today. Here we go:

- Core assumption #1: the imbalance between supply and demand for skilled software developers keeps cranking up their price tag. This local demand is a reaction to the same wage inflation in developed economies.

- Core assumption #2: The leaving employee was a solid performer, ie. someone the firm wanted to keep.

- She left mostly to comp reasons. Her dissatisfaction with the subpar compensation was the primary trigger, while the motivation side was okay. (ie. no graveyard shifts, no regular weekend work, fine boss, cool environment and mostly a cool job with ownership)

- The function the leaving employee filled in is still necessary and the firm is NOT in crises mode when any voluntary departure is cheaper than a layoff with severance payments. Caveat: your best people will be the voluntary leavers while the not so good might stay.

- It takes 4-6 months to ramp up a new employee to do the same thing his/her predecessor did.

- Even a devoted employee takes off her foot from the gas during her resignation period, hence I used a 50% multiplier for her last month.

- The cost of a backfill is cca. 2 months gross base compensation. You pay it as a mix of agency fee, referral bonus, cost of your own recruiters, but you pay it anyway.

- The backfill will cost you 20+% more than the guy who left. 15% is the psychological threshold, read a risk premium to jump ships. (I have seen several cases beyond 35%.)

- I calculated with a 4 years period; under developer terms this is a long tenure.

Items that I did not include in the model, but I think it would strengthen my argument:

- The model does not include the time investment (that is also money) needed from the existing employees to ramp up the newcomer.

- I left out the most important hidden cost, the lost revenue from the delayed delivery. The reason: I could not produce a model that would be accepted by any finance people.

- I skipped the value of the institutional knowledge that left with the leaving employee.

- I ignored the collateral damage: the cost spike will create internal tensions if it leaks out. In Hungary it surely will. A bad thing.

- I ignored the gains and losses from the FX rate fluctuations (ie. when the budget is in USD while comp is in HUF.)

Appendix B – input parameters in the model

Appendix C - references

Hungary Gross Average Wages Growth https://tradingeconomics.com/hungary/wage-growth

http://goaleurope.com/2016/10/26/software-developer-salary-europe-survey-results-2016/

https://www.daxx.com/blog/development-trends/it-salaries-software-developer-trends-2019

https://qubit-labs.com/average-software-developer-salaries-salary-comparison-country/

https://www.hwsw.hu/hirek/57000/hays-salary-guide-fizetes-berek-bertargyalas-hr-fejlesztok-2017.html

https://www.hwsw.hu/hirek/58596/hays-salary-guide-informatikus-fizetes-berek-2018.html

https://www.hwsw.hu/hirek/60222/informatikus-fejleszto-rendszermernok-fizetesek-berek-2019.html

https://cloud.email.hays.com/hu_salary_guide