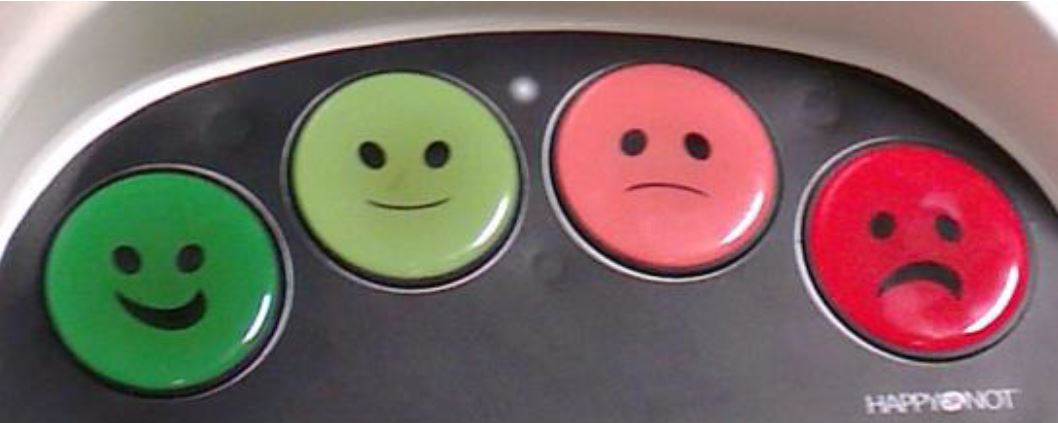

A few weeks ago in a customer care related discussion I proposed a mini customer satisfaction survey, something like this one on the right. The idea was a copycat; I saw this simple customer feedback idea at Heathrow airport.

I figured it was great since it allowed the customers to express their opinions in a second, while you could log the time when the feedback arrived, ie. you would know which shift generated the feedback. Guess what the answer to my suggestion was: “We don’t have the resources to do anything with that feedback anyway, so this is better not rattling the cage in the first place…” Ouch. As my father used to tell “anger without power is folly” so I wrote this blog post instead.

According to Mary Poppendieck there are three easy ways to piss of a client:

1. reduce the quality of service (eg. your telco sells you an 8 Mbit ADSL that in fact is 3.5 Mbit)

2. overcharge for the service (your telco still charges as if their service was indeed 8 Mbit)

3. keep the client in anxiety (your telco provides LTE in your area, but with a small data limit and without a Wi-Fi router (with a few Ethernet ports and a built in LTE modem) and it does not let you off the hook with your existing contract.

The result: you buy an LTE based internet service from ANOTHER telco and show the middle finger to the first provider (and you feel good for a moment). Learning: the client is a human being and humans are predictably irrational if you push them over the limit.

In the following example I will refer to examples from the imaginary ACME Corp. Disclaimer: Any resemblance to actual firms is purely coincidental.

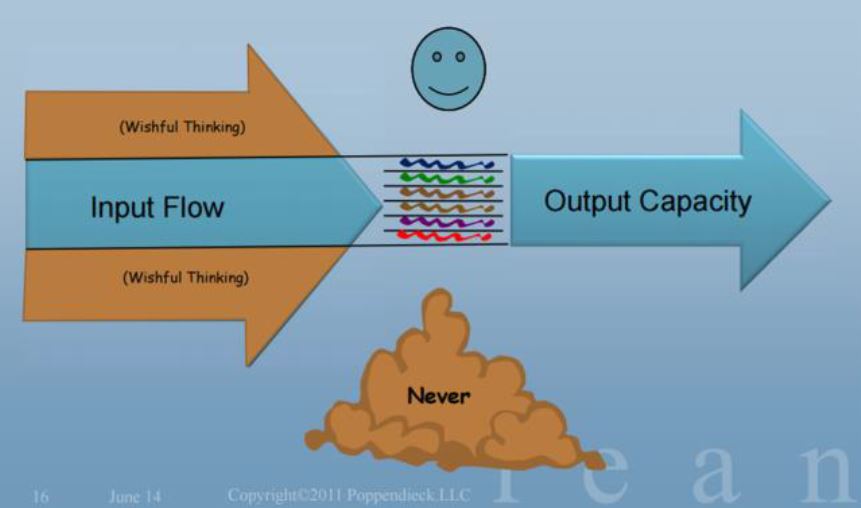

At ACME the Jira queues of IT are graveyards of dead wishes, some items are 2+ years old; you can bet that even the requestors forgot about them, let alone if they are still with ACME. As Mary puts it anything beyond the output capacity of a service component is wishful thinking: the surplus will never get executed.

On the other hand this setup guarantees customer anxiety: unpredictable delivery times “when my service request will be served?”, using the “who shouts loudest will be served first” method as selection criteria to work on any item topped with employee frustration: “ever changing priorities, clients are bypassing the queue with ad-hoc requests allowing no self-accomplishment.” This setup at ACME is not new, after several years it made its way to the genes of the organization: top performers are those who are good at fighting fires, but not so good at resource planning. Okay, we have dissatisfied clients and dissatisfied staff (and these folks vote with their feet), so what shall we do about it? (Relax, this is at ACME.) Let’s have a look at what others have suggested to solve a similar problem in manufacturing.

This blog post is based upon the book by Eliyahu Goldratt, the Goal. I am not going to summarize this

brilliant novel here (I suggest you read it for yourself); I just name a few concepts necessary to carry on.

Productivity is accomplishing your goal: to make money. You can play with the following three levers to

make it happen:

- Throughput – Is the rate at which your company generates money through selling products or

services. - Inventory – the money your company has invested in purchasing things which it intends to sell.

- Operational Expenses – the money your company spends in order to turn inventory into

throughput.

Now imagine a hiking experience with a bunch of Boy Scouts, one of them being Herbie. During the hike,

you notice that the line of hikers is stretching longer and longer as time passes. You recognize that one

particular scout, Herbie, is the slowest hiker in the group. Herbie holds up all scouts behind him. One

would think that even though these hikers all walk at different speeds, their average rate of progress

should be estimable. This average rate should become the nominal rate of progress for the entire team.

Instead the troop is completing the hike at the rate of its slowest member, Herbie. Herbie is being left

behind at a longer and longer stretch because he can't go any faster. Herbie is a CONSTRAINT. If you

want to reach your goal - in this case the entire team arriving at a camp site before sunset - you need to

eliminate the constraint – in this case by redistributing the stuff in Herbie’s backpack to other kids and

by placing Herbie at the front of the troops. It may sound a bit extreme, but the same principles are at

work in the Boy Scout hike example, in the operation of a manufacturing plant and in running an IT

shop. Learning: Constraints will define the overall throughput of your system. Identifying the

bottlenecks in your operation (finding Herbie) is the first step in improving the throughput of your

business, regardless if this is a hiking trip, a manufacturing plant or an IT department.

Viewing an organization from the operating expense perspective causes one to believe that an

organization is composed of independent variables. But viewing the organization from the throughput

perspective will make you realize that the organization is a collection of dependent variables where an

action targeting one of these variables could have a significant effect on the throughput of the entire

system. An example: In the Hungarian medical system someone in his infinite wisdom figured he could

save money by banning the repair of resectoscopes (they are expensive) that were used to carry out

TURP (transurethral resection of the prostate) to cure BPH (benign prostatic hyperplasia). This decision

forced the docs to go back to the traditional open surgery with ten times the hospital treatment cost,

the healing time and the chance for complications. Cost saving mission accomplished, right? WRONG.

Learning: Partial efficiencies are the number one enemy of overall productivity.

Managing the parts of an organization as if they were independent is not the right thing to do if your

goal is to increase the throughput of the org. If you want to increase throughput you must define the

real goal of your entire group and then you must find and eliminate (by increasing the performance of)

your constraints being in the value stream producing that throughput.

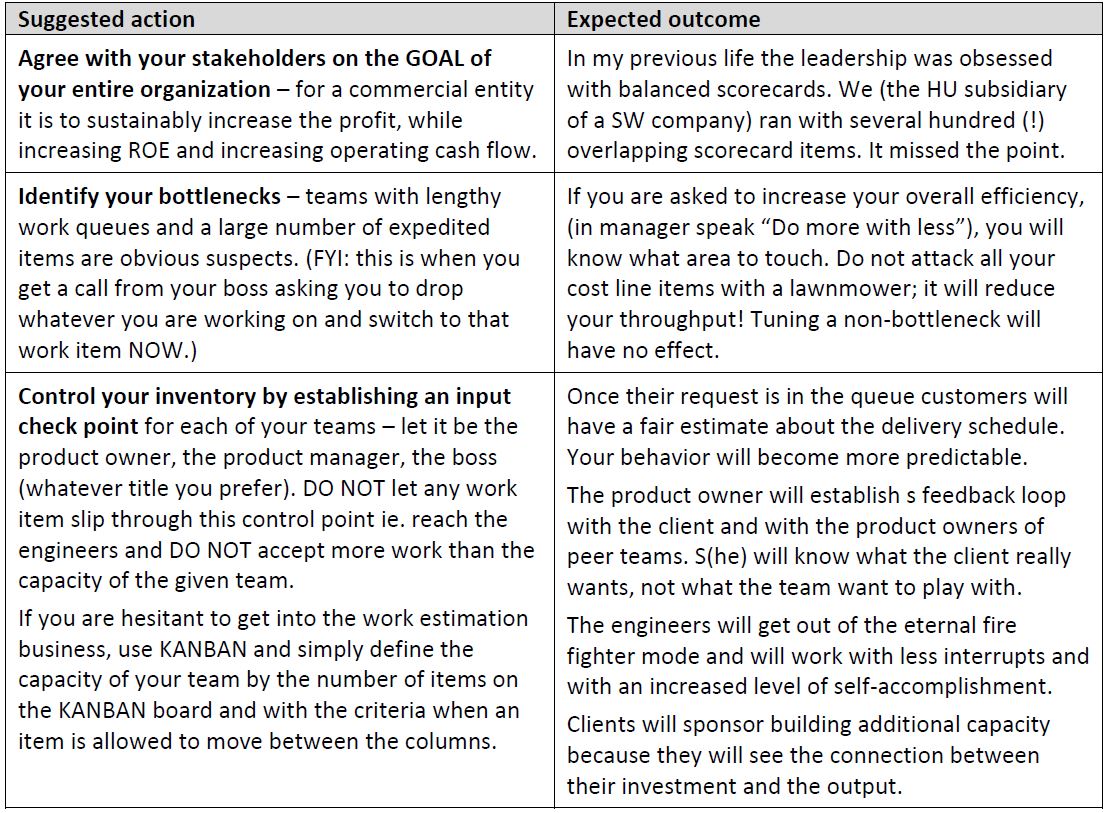

We learned the following so far:

1. Keeping the client in anxiety is a guaranteed way top piss them off.

2. A properly upset client will react, so unless you are an unchallengeable monopoly, you risk your

business. (Ignoring this fact triggered the whole post.)

3. Maintaining work item queues beyond the capacity of a given service provider is a proven

method to annoy your clients (and your employees).

4. Constraints will define the overall throughput of your system.

5. Going after local efficiencies will undermine your overall productivity.

The rest of this post is just speculation on what I would do if I worked for ACME. I realize this is pure

theory (although supported by another book named the Phoenix Project) So here we go:

I dreamed enough for today. If you happen to have the appetite to test the above suggestions in your

daily life, pls. let me know. I would be happy to assist you. As always I appreciate any feedback on this

blog post.

References:

- https://www.slideshare.net/AgileOnTheBeach/value-stream-mapping-9358435

- http://www.poppendieck.com/workshop.html

- https://www.amazon.com/Goal-Process-Ongoing-Improvement/dp/0884271951